At the end on Crete he took to the hills, and said he’d fight it out with only a revolver.

He was a great soldier …

“I wonder,” mused my brother a few years ago now, “whether things would have been different if we had had uncles.”

I stopped short. I treasured my two aunts. Mostly for their abundance of attitude. Would my brothers, likewise have respected and revered their uncles had they had them?

Last year I reflected a little on the life of Uncle Charlie.

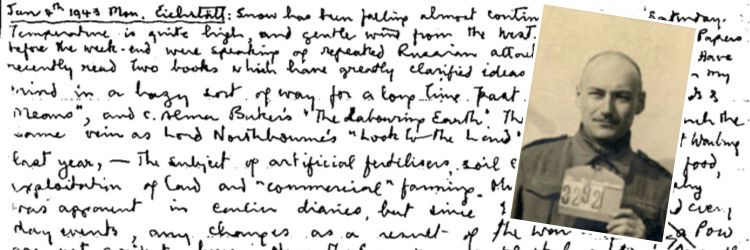

Uncle John’s diaries are his very personal story. But can I put his story in the broad context of the war? What were the conditions like in Germany at the time? How were the prisoners treated? Did this differ from camp to camp – Uncle John spent time in four officer camps:

Oflag XC Lübeck

Oflag VIB Warburg

Oflag VIIB Eichstätt

Oflag IX A/Z Rotenburg

In June or July this year I hope to follow John Learmonth’s restricted World War II journey through the German country side. This post is my starting point.

I would love to hear suggestions as to what might add value to what Uncle John wrote in the diaries that have survived him.

We know that John Learmonth wrote eleven diaries before he died in May 1944. We don’t have them all. Nor do the ones we have cover all of Uncle John’s experiences.

At the beginning of Diary 3 and on 3 November 1939 John Learmonth wrote about his previous diary (Diary 2):

I cannot remember when I wrote the last entry in my previous diary, or even what I wrote about. That diary will probably be found amongst my other possessions at Carramar, Tyrendarra, Vic.

John confirms in later diaries that he sealed his first two diaries and sent them home with the rest of his possessions at the time he transferred from the Militia to the AIF. We assume they were later destroyed.

Uncle John’s Diary 3 covers the period from when he attended training at Seymour until he sailed from the Clyde on the Empress of Canada for Egypt. At the beginning of his Diary 4 he wrote:

My third diary, covering the twelve months (approx) ending 19/11/40, is with me now and will probably remain with my possessions wherever I go until the end of the war.

This was not to be the case. Written when he was a prisoner of war in Germany entries at the beginning of Diaries 8 and 9 indicate that Diary 3 was in his uniform trunk which was stored in the AIF kit store in Alexandria. However, this diary must have become separated from his kit for John wrote

Mum says my diary has been removed from my trunk returned from Alexandria.

The original of Diary 4 is held in Russian Archives. A copy was given to the family in 1998. It covers John’s Greek and Crete campaign but not, alas, the final two months leading up to his capture in Crete on 30 May 1941. Perhaps mindful that his diaries were being read by the German censors Uncle John recorded in Diary 9 that he had destroyed Diary 4

on being captured in Crete in May 1941.

Diaries 4 & 5 were probably destroyed in the Parcels Office fire. Just be careful here:

The fourth I destroyed on being captured in Crete in May 1941 and subsequently rewrote as the 4th and 5th while in Salonika.

Uncle John was in the Salonika Transit Camp in northern Greece 11 June to 22 July 1941. This was a large transit camp where the conditions were appalling. The prisoners were starving and covered with lice and other bugs. They received no letters, no food parcels from home nor any Red Cross parcels.

The rewritten Diaries 4 and 5 together with Diaries 6 and 7 were confiscated on Uncle John’s arrival at Oflag XC Lübeck. This camp was located near Hamburg and Uncle John was there for 6 weeks – 29 July – 8 October 1942. The conditions were better than Salonika but rations were minimal and still there were no food parcels nor any Red Cross parcels. On the nights of 7 and 8 September 1942 the Parcels Office in the Lübeck camp caught fire and it seemed that John’s diaries had disappeared forever. On 4 December 1942 he wrote

I regret very much losing the diaries preceding this one (No 8). They throw an interesting light on my state of mind when first taken prisoner. Although I am now well on the way to re-writing them I cannot entirely recapture the atmosphere of that period.

Despite the loss of his previous diaries John handed a completed one in for censoring at his new camp Oflag VIB Warburg – near Dossel in Westphalia. John’s trust was rewarded as it was eventually returned to him. Uncle John arrived at Warburg on 9 October 1941 and stayed for 11 months. Here Red Cross Parcels started to arrive – together with the first of many letters and parcels from home.

Uncle John moved yet again – to Oflag VIIB Eichstätt for ten months until July 1943 and finally to Oflag 9 A/Z Rotenburg for the ten months until his death there in May 1944. During this period he wrote his last three diaries – Nos 9, 10 and 11.

John Learmonth is remembered in Hanover Cemetery looked after by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

No story about Uncle John is complete without including John Manifold’s elegy. Yes, there is a story in the words written but the genius of the poem is in its form – based on the Classics? The form accentuates the emotions expressed. From the second verse look at the first and third lines. They rhyme with the second line of the preceding verse:

This is not sorrow, this is work: I build

A cairn of words over a silent man,

My friend John Learmonth whom the Germans killed.

There was no word of hero in his plan;

Verse should have been his love and peace his trade

But history turned him to a partisan.

Far from the battle as his bones are laid

Crete will remember him. Remember well,

Mountains of Crete, the Second Field Brigade!

Say Crete, and there is little more to tell

Of muddle tall as treachery, despair

And black defeat resounding like a bell;

But bring the magnifying focus near

And In contempt of muddle and defeat

The old heroic virtues still appear.

Australian blood where hot and icy meet

(James Hogg and Lermontov were of his kin)

Lie still and fertilise the fields of Crete.

Schoolboy, I watched his ballading begin:

Billy and bullocky and billabong,

Our properties of childhood, all were in.

I heard the air though not the undersong,

The fierceness and resolve; but all the same

They’re the tradition, and tradition’s strong.

Swagman and bushranger die hard, die game,

Die fighting, like that wild colonial boy –

Jack Dowling, says the ballad, was his name.

He also spun his pistol like a toy,

Turned to the hills like wolf or kangaroo

And faced destruction with a bitter joy.

His freedom gave him nothing else to do

But set his back against his family tree

And fight the better for the fact he knew

He was as good as dead. Because the sea

Was closed and the air dark and the land lost,

“They’ll never capture me alive,” said he

That’s courage chemically pure, uncrossed

With sacrifice or duty or career,

Which counts and pays in ready coin the cost

Of holding course. Armies are not its sphere

Where all’s contrived to achieve its counterfeit;

It swears with discipline, it’s volunteer.

I could as hardly make a moral fit

Around it as around a lightning flash.

There is no moral, that’s the point of it,

No moral. But I’m glad of this panache

That sparkles, as from flint, from us and steel,

True to no crown nor presidential sash

Nor flag nor fame. Let others mourn and feel

He died for nothing: nothings have their place.

While thus the kind and civilise conceal

This spring of unsuspected inward grace

And look on death as equals, I am filled

With queer affection for the human race.

The Tomb of Lieut. John Learmonth, AIF

by John Manifold

2 responses to “Lieutenant John Learmonth of the 2/3 Australian Field Regiment”

I have included your blog in INTERESTING BLOGS in FRIDAY FOSSICKING at

https://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com/2018/04/friday-fossicking-6th-april-2018.html

Thank you, Chris

I love the whole concept of your blog…very creative.

I went to the funeral of the last of Uncle John’s cousins recently. I realised that I have no-one left to tell me of their World War II experiences. I had concentrated on my World War I ancestors. Now I must capture the Vietnam stories of my own generation before they are gone and forgotten. Stories they tell are never quite as I imagined from the outside but always give substance to the bare bones of my family tree. So thank you Chris for your kind comments and for spreading the word.